portraits of young women as (NOT) dolls – about Gøril Fuhr's paintings

::: Gøril Fuhr (photo: Szilvia Josvai)

- - pictures are stories

Just like movies, paintings have always been narrative spectacles. A painting will tell a story too, offer a “trip” which the viewer can go through, experience from “inside”, identify with its characters, protagonists, as well as with the subject of the artist. This “narrative” aspect is equally valid for classicists war scenes, St. Sebastian executions, triptychs, and for portraits and still lives, and even abstract paintings, or images in magazines. We only have to accept that not only “adventures of protagonists” are stories but basically anything that does the same thing as stories do, that is, giving you a picture, a report on reality which will become your experience.

Think of Van Gogh's Bedroom in Arles, isn't that a story? Or the Pair of Shoes(s), or think of Jan van Eyck's portrait of the Arnolfini couple. Viewing an image is a complex and intelligent activity by which we explore reality. That's how images work, and that's how our mind interprets them. This is even true for viewing an abstract image like Malevich's White on White, cause the viewer's “trip” also includes reflecting on the viewing itself, on the discussions, on the reactions of the public, by which s/he sure explores reality, gathers intel on the world surrounding her or him.

So, it is not a bold statement after all that as poetry and literature have always been visual arts, likewise and consistently, visual arts have been art forms of narration, story telling, offering “trips” for our empathy, imagination and thinking.

::: "After the Bath"

- - introspective openness

What strikes us at Gøril Fuhr's exhibition is the ease by which the images suck us in into their world, into the stories that they – like Proust's madeleine – hold and convey. Given the fact that she's based in Oslo, that is, she's Nordic – which stereotypically stands for being natural in contrast to the “Southern-Europeans” – somehow we're not that much surprised that such self evident compositions, such easily perceptible stories can appear on her canvases. As if the artist didn't have to bother too much with “the state of art” – with defending her images and fixing a place for them in the canon – and could purely focus on the story she wanted to capture and share.

Whatever we might think based on our Nordic stereotypes, as we go on tasting her images, we'll step by step realize that the powerful solemnity flowing out from the pictures has nothing to do with the artist's location, and that it's only about the good old artistic sincerity, the openness by which the artist exposes her/himself and invites the viewer to step into her/his world and to look around, as if whispering: “hey, the door is open, come inside, be my guest”.

- - silent expressivity

This kind of artistic sincerity is also very expressive cause it skips making defensive efforts to cover what's being said while it is being said, and so the “message”, the statement of the expression can be million times more straightforward and blowing. And although one wouldn't like to fall for the trap of stereotyping, it would be hard not to think of another great Nordic artist's work, Mot Naturen (Out of Nature), a film by Ole Giæver in which the introspective artistic sincerity, as well as being not afraid of nature and nudity – the persecution of which, with the beautiful exception of Nordic cultures, totally dominates the Western behavior – was likewise blowing.

::: at the Gallery Laszka -- back in April

Expressivity of this kind, non-theatrical, cool and subtle – yet frontal – can be really surprising. And refreshing. What you see, turns out to be what you think it is. No purposely covered meaning in the background to dig for, it's all there, openly, “x equals x”. The artist really meant that. And at the opening, before you would have started to think about whether those self portraits were really self portraits or “just” projections of the artist's self, you had caught sight of Gøril Fuhr in person wearing a hair ban similar to what that burnt out, sad girl has in one of these (self) portraits, “With Wedding Ring”. By this, she linked herself to her images as if saying “yes, they're personal, they are kind of autobiographical”. It all felt completely natural, just like realizing, as the credits of Mot Naturen were rolling, that the mother of the boy was his real life mother. X equals x.

That picture with the hair ban, by the way, could as well be called “in the middle of the journey of our life”, cause after a series of non-Bechdelian scenes (about getting married, to a guy) this one is like a “mission completed” stage, and having seen all those children portraits, even the bigger picture becomes visible: a complete cycle with kids, girls, women, and giving birth. This subtle but unmistakeable obviousness only makes your fascination grow. Expressivity – we might realize – is not about the loudness but the clarity of the expression.

::: "With Wedding Ring"

- - self portraits, half of a woman's life

At the exhibition, there were two sets of paintings. Portraits of children, typically girls – of various ages, from about 4 to 16 or so – and self portraits. Although the self portraits were put last in the classy downstairs room of the Gallery Laszka, they would get you first. They depict... womanly situations, stages, turning points of one's live – of a woman's life.

They playfully resemble classic paintings, like gothic Madonna pictures (without the baby, of course), renaissance portraits, including subtly even Vermeer's letter reading girl, even if for the theme only. The point seems to be that anything is possible, we're sort of detached from our time. A Madonna picture meets a contemporary artist's expressive self portrait. The “object”, instead of being an object, depicts herself – in a conscious, intense, self-reflecting mode.

Despite the world famous good standing of gender equality in Norway (or rather, according to that), these depictions are openly feminist – and straight down existentialist. They explicitly raise the question whether at “half-way upon the journey” of a woman's life, upon completion of the wedding & pregnancy project, a kind of a hollowness is natural, and whether this project should really take one half of a woman's life, or it could be perhaps just part of that (which in Norway seems to be the case).

- - kids in the void

The children portraits, like it happens frequently in woman artists' images (another stereotype, sorry), look subtly weird and “spooky”. The dreamish effect, however, unlike usually, when the images simply remind us of thrillers and horror movies (by the means of lighting, costume design or/and scary environment like forests, the prototype of which we can find in Van Gogh's Girl in the Wood), comes from an organic source: from reminding the viewer of old time photographs. It is as simple as that, and it works perfectly.

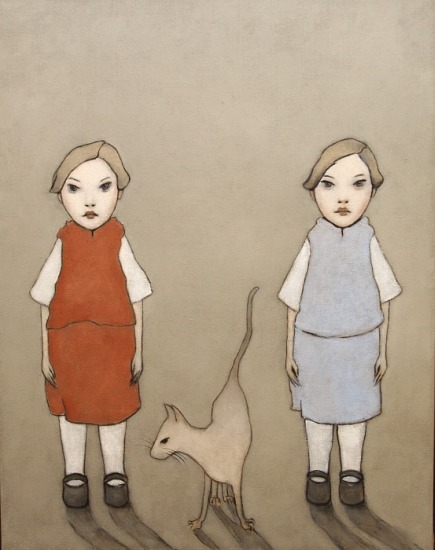

We see kids in an imaginary photo studio in front of solid “backdrops”, they are rigged up with the usual accessories – if a turtle on leash could be called that – seated on a table or standing, sometimes even outdoors (see the Chinese kids series) but in a strange, sci-fi like environment, with very tricky lighting. As a general effect, the kids are sort of taken ... out of their realities, out of their lives. They are desolate. Floating in the void. Some place else. It is dramatic, and sort of traumatic too, yet it is peaceful. We like these kids, we love them, feel for them. They are like our friends, we relate to them horizontally, not as adults to kids but as adults to adults – which is a major psychological device.

We have no clue which year it could be, but we can feel that what we see is the past. That is, these girls, these kids, as we see them, don't exist anymore – the core element of the aesthetics of a photographic portrait here becomes the source of an overall sadness, but not exclusively.

- - deviance

Girls in Furh's paintings do have concrete reasons to be sad too. As for the child portraits, a photographer (in the imaginary portrait photo studio) tries to make them look like someone else that they are not. The same role conflict is present in the self portraits too, the woman is supposed to fulfill the expectations, play her role, be that thing that she's not. “She's supposed to be happy. But she's not.” – this is the caption that would fit any of the portraits. Just look at the beautiful “After the Bath”.

The kids also reflect on themselves as they are being depicted, it's like a dress fitting. Their souls, their identities hurt cause they don't exactly match the image that they are expected to be. They look like dolls, but they are not. They are deviant. And so “are” the “women” of the self portraits.

::: "Chinese Kids"

- - sophisticated iconography

Fuhr has developed a sophisticated iconography, she has created a visual world, a system of her own signs, and she uses it as an orchestra. Every detail of her pictures intensively takes part in delivering the “message”, the story. Moreover, the details are all at the same (top) level, they equally play main roles. A subject's lips, a cat, a leash, a colorful beach ball, hands, shoes, they are all major parts of the image, not simply as details but as individual motifs, “co-characters”. Every part of the image “works on the same project”, that is, expressing the subject's state of mind, her story, letting the viewer taste what it could feel like to be her, “what it feels like for a girl”.

Fuhr's faces and characters are iconic, well defined with elaborate psychological details (amplified by the consonance with the other motifs). We can understand them right away, empathize with their personalities, identify with their stories as smoothly and intimately as listening to a Suzanne Vega song – take Luka for example.

::: DETAIL from "At the Drawing Table"

- - sharp dramatism

Fuhr's minimalism serves intensity, she's just omitting redundancy, only keeping details which could be used as evidence supporting the story. Sharp, cartoonesque outlines of the figures, as well as the form that a jumping rope or a leash happens to take, or the tail of a cat, the soft shape of a beach ball, or the hands in the self portraits, they generate acute tension. Originally loose forms maniacally contrived, forcefully finalized, as if carved by a sharp pencil into some soft surface. They turn the sadness into drama. They express the vulnerability of the subjects – and, by the way, that of the artist, too. Look at the clone-like parallelism of the Chinese twins' haircuts. Isn't it as if they were victims somehow? Don't the sharp lines amplify this to the extreme? Look at that hand in “By the Drawing Table”. The sensitivity that her hand reflects is immense. So fragile, so vulnerable – in contrast to the visually rigid, gloomy and hollow environment. The silent calmness is just the surface. It's like a scream in a padded room that you happen to hear from outside. Not a chance for the viewer to avoid empathy.

Gøril Fuhr's images, her stories and her scenes – as we have experienced it – will go instantly under your skin, and, as it turns out long weeks after the encounter, they'll also persist.